Air temperature is easy to measure and often misleading. In refrigerated storage, transport, and retail display, the air can swing quickly when doors open, fans cycle, or defrost runs, while the product temperature changes more slowly because of thermal mass. In audits and incident reviews, there is repeatedly the same failure: organisations monitor air temperature and assume they have monitored food safety. Air responds quickly; product responds slowly. The gap between the two is where unnecessary waste and genuine risk both occur.

Food safety monitoring needs “product temperature”, not air temperature. And it should be wireless.

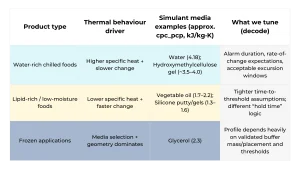

In cold rooms, fridges, display cabinets, and transport, air temperature changes faster than the product itself. That is why many HACCP programmes rely on product simulants: materials that mimic the thermal behaviour (thermal inertia) of real foods, so alarms and reports reflect actual product risk rather than short-lived air spikes. A useful wireless monitoring product, food simulant is thus a controlled approximation of thermal inertia. The technical literature and industry guidance typically frame this around specific heat and geometry: water-dominant foods behave differently than fatty products; a thin pack responds differently than a dense block; and the “best” simulant depends on what you are trying to represent and validate. In other words, there is no single perfect simulant, there is only a best-fit simulant for a specific product category and use case.

The ambient temperature can swing quickly when staff opens doors, while the product temperature changes more slowly because of thermal mass.

What to look for in a wireless monitoring food simulant

From a food-safety and operations standpoint, the requirements are predictable:

-

Thermal inertia that is physical, not cosmetic (a real buffer, not just smoothed readings).

-

Wireless deployment at scale (so the monitoring plan is driven by risk points, not cabling constraints).

-

Sealed, hygienic hardware (cleaning realities, condensation, spills).

- Audit-ready evidence (reliable logging, context, and documented placement rationale).

These requirements are predictable because they address the usual points of failure. Thermal inertia must be physical, because software smoothing can hide the difference between air fluctuations and true product behaviour. Deployment must be wireless at scale, so sensors go where risk is highest rather than where cabling is easiest. Hardware must be sealed and hygienic, because condensation, spills, and cleaning quickly defeat exposed connectors and enclosures. Finally, the system must produce audit-ready evidence: continuous, reliable logs with enough context (and documented placement) to explain excursions and defend the monitoring approach.

A good wireless monitoring food simulant sensor mimics product inertia, is easy to deploy, and produces audit-ready logs.

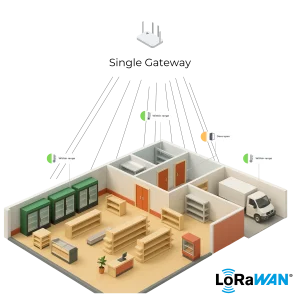

LoRaWAN is the perfect connectivity for scaling food safety monitoring systemsin HoReCa.

The available options out there:

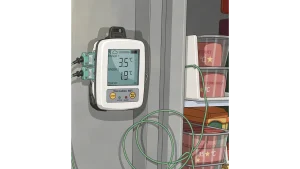

1) Wi-Fi / logger-based systems (e.g. Testo): credible instruments, but fragmented and not IoT-native

Testo and similar systems are typically built around Wi-Fi or proprietary logger workflows: battery loggers with internal or cabled probes, talking to a base station or cloud. They are strong as measuring instruments and for spot checks or small systems, with good accuracy and calibration options.

Usually architected as logger + software, not as a fully integrated, low-power IoT node for large estates. For continuous HACCP monitoring across many cabinets and rooms, this can mean more gateways, more manual handling (downloads, Wi-Fi setup, batteries), and fragmented integration into wider facility or IoT platforms.

2) Wired food simulant probes (credible sensing, operational friction)

Typical examples are food simulant probes (e.g. ETI): intentionally slow-response to simulate food temperature, reads -20 to 100 °C, and is stated as ±0.4 °C accurate (with further accuracy bands). It also comes with a 1 m lead and assumes you connect it to an instrument/logger workflow.

For audits, this can be acceptable, but it often limits coverage: the more cables and manual routines you require, the fewer points stay consistently monitored over time. These solutions are credible at the sensing element, but the overall system often becomes a combination of probe + cable + handheld routine or probe + separate logger, and deployments tend to concentrate where cabling is least painful.

Wired probes but often limit coverage: the more cables and manual routines you require, the fewer points stay consistently monitored over time.

3) Wireless probe extensions tied to a base device/platform (better, but multi-part)

A food simulant probe (e.g. MachineQ) is positioned as a flex sensor extension for simulating core food temperature in refrigerators, with a stated operating range of -40 to +60 °C and up to 5 years on a replaceable battery.

This can be a good fit inside an enterprise ecosystem, but it is still architected as an “extension” (probe + bracket/base + platform).

4) STB10: a fully self-contained wireless monitoring food simulant over LoRaWAN

STB10 is designed as a dual-channel food-simulant sensor: it measures buffer temperature (via a glass-bead filled thermal buffer) and ambient temperature, explicitly to mirror thermal inertia and reduce false alarms in HACCP decisions.

Operationally, it is built around what a wireless monitoring product / food simulant needs to be in kitchens, cold rooms, retail, and warehouses: LoRaWAN (1.0.3, Class A), IP67 sealed enclosure, battery operation targeting up to ~7 years, and onboard data logging with configuration via NFC and downlink.

Senzemo STB10 sensor, is an advanced food-safety temperature sensor engineered for professional kitchens, hotels, central kitchens, food production, and HACCP-regulated environments.

Specific Heat

Specific heat (cₚ) is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by one degree Celsius (1 K). It determines how quickly a material heats or cools, influencing how closely a simulant mimics real food behavior. Each food has a unique specific heat depending on its composition; particularly its water, fat, protein, and carbohydrate content. Foods high in water typically have higher specific heats and respond more slowly to temperature change, while fatty or low-moisture foods change temperature more rapidly.

Categories differ (water, fat, solids, geometry), specific heat is the key parameter and provides practical reference values: water (~4.18 kJ/kg·K), oils (~1.7–2.2), glycerol (~2.3), various gels (~3.5–4.0), and glass beads (~0.7–0.9), among others. A practical way to use this in a monitoring programme is to keep the deployment hardware consistent (so installation and maintenance stay simple) while using decoder/application logic to implement a “product profile” for alarm behaviour and reporting—i.e., treat the wireless monitoring product / food simulant as the stable instrument, and treat “best simulant” as a validated configuration.

Using decoder to mimic real food behavior depending on the category and composition.

Conclusion

If you want continuous, scalable HACCP evidence, the main differentiator is whether the wireless monitoring food simulant is genuinely deployable without cable work and without hygiene compromises. STB10’s combination of dual temperature (buffer + ambient), LoRaWAN, sealed IP67, onboard logging, NFC/downlink configuration, long battery life, is an uncommon “all-in-one” package for this category, and it is the reason it tends to reduce false alarms while increasing coverage.

Senzemo, together with our Australian partner MFC Safe already works with high profile clients.